Talking to machines

Let’s assume that you are fluent in Tobe, a machine language. How would you use this language to talk to a machine? What would you say? Is it even possible to learn a machine language without an understanding of how machines work, how they think?

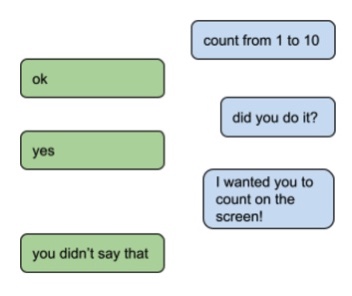

How would you instruct a machine to “count from 1 to 10”?

Machines are really good at counting, so it shouldn’t be an issue.

You could write a program. Choose your favourite programming language, and code it up. Or, you could hire an IT developer. That’s a good way to talk to machines without having to understand how they work. And just think! An IT developer, maybe a whole team of developers, can do a lot more than churn out silly little counting programs – you just need to talk to them! But how?

How would you instruct an IT developer to “count from 1 to 10”?

IT developers are really good at counting, so it shouldn’t be an issue.

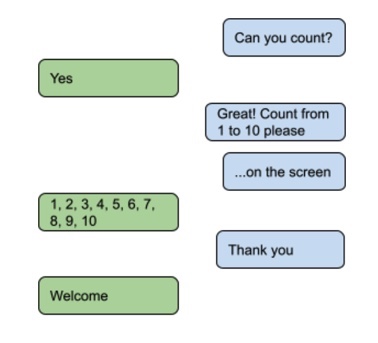

And of course, it isn’t. You’d just write a specification and ask the developer to implement it. Think of it as a little interview test: “Can you write a program that counts from 1 to 10? You can? You’re hired!” Machines are a lot like IT developers. We’ve already established that they are good at counting, and they can do a lot of other things like pattern matching and drawing, and holding on to secrets (mostly), and opening doors, and closing doors. But if you don’t want to program machines directly, or hire somebody else to program them, then you’re going to have to talk to them.

So I’m asking, not in a “what does it feel like to be a bat?” kind of way, but perhaps with a nod in that direction, how would you talk to a machine? How would you instruct a machine to “count from 1 to 10”?

Let’s assume that you have selected a machine, and you submit the instruction “count from 1 to 10”. The machine accepts the instruction, which is a good start, but informs you that it doesn’t know what the word “count’’ means. You scratch your head and, thinking vaguely of computers of yore, ask “do you know how to accumulate?”. Well, it turns out that this machine does know how to accumulate, so you say “counting is a lot like accumulating”. The machine accepts this new information and begins to accumulate using its internal registers. But no sooner than it has started, it crashes and reboots without warning. After much investigation, it transpires that the machine can use its registers to count but you have to instruct it to store its current value on the stack before starting a new function and restore them when it completes. Otherwise: boom!

A self-contained kind of dialogue – let’s call it a script – is emerging from this conversation. This script contains all of the information and all of the constraints needed to ensure that the machine executes our instruction as expected:

counting is a lot like accumulating

store registers before entering a function

restore registers on return from a function

count from 1 to 10

Is this the kind of dialogue that we need to have with a machine in order to produce reliable results? Is this not just another programming language? Before attempting some kind of an answer, imagine for a moment that you are talking instead to that imaginary IT developer we just hired. Let’s assume this developer understands the concepts of functions, registers, and accumulating, accepts the challenge, reads the script above, and effortlessly produces a machine-code application. Perhaps something along the lines of:

push registers

push 1

push 10

call accumulate

pop registers

Or maybe our developer is more comfortable with JavaScript than machine code. And, recognizing that those register instructions are redundant in a higher-level language, produces a more compact and pleasingly semantic:

var count = accumulate;

count(1,10);

Nice! I guess it all depends on the imaginary job spec you put out to hire the imaginary developer in the first place. You might have subconsciously posted: “machine code developer required…” on the grounds that we are substituting for a machine and we need somebody who understands how machines work. Or you might have taken a more pragmatic approach by reviewing the script yourself and, concluding that in this case, a language that abstracts over these low-level implementation details would be more productive, you decided to post: “JavaScript developer required…”.

Either way, each of these hiring scenarios suggests at least one way to talk to machines without having to actually understand how they work. When we talk to IT developers, we do not need to know how they work, or even how they think, because we share a common language that allows us to share our intentions and, presumably, discuss them so that we can come to a mutual understanding. It is a language so powerful and expressive that we can establish said intentional understanding in a very concise and efficient manner, and it has to be applauded that no part of this communication or its subsequent development contributed to the IT developer’s overall risk of keeling over and rebooting. This is the kind of language that we need to use when we talk to machines.

One language specifically designed to communicate the subtlety and nuance of third-party intentionality is Tobe. Tobe is a machine language1 that has been constructed to support and promote reliable communication between parties that might include people, imaginary IT developers, and machines. In Tobe, every statement is intentional, and every intention is projected onto an imaginary shared third-party. If I say “count from 1 to 10” in Tobe, then I am projecting this not to the machine, but to a shared third-party that both the machine and I have access to. Tobe ensures that my understanding of the intention is directly translatable to the machine’s understanding of the same intentionality. If there is a significant difference of understanding, it is one of perspective encoded directly into the information exchange. At no time is the machine at risk of keeling over and rebooting.

In Tobe then, we have a reliable and efficient communication channel with a machine – and it looks a lot like English. The machine understands the intention, and if it additionally understands how to count then it will diligently2 execute the instruction and you can stop reading right here. But if it doesn’t know how to count, then it will use the same channel to inform us and so we still really haven’t answered that leading question; ”How would you instruct a machine to count from 1 to 10?”.

And this is a question that has vexed me throughout the writing of this article. Because, unless you are lucky enough to have stumbled across a machine that understands how to program, you are in for a very tough job in teaching it how to count.

Let’s assume that we used Tobe as a communication channel to interview machines and through that process we selected a machine that understands machine code. In this scenario, scenario 1, we can simply instruct the machine to count from 1 to 10 and it will (again, diligently) generate an application that looks a lot like the machine code solution described earlier. Or, scenario 2, we select a machine proficient in JavaScript. Again, because we have selected a machine that is able to translate high level intentionality into lower level code, we will be presented with a workable JavaScript solution. Both are favorable outcomes. In each scenario, talking to machines is a lot like talking to people.

But then there’s scenario 3. In which we do not manage to find a machine that can code. How would you instruct a machine to count from 1 to 10? A MACHINE THAT CAN’T EVEN CODE!!

And the answer seems to be: diligently. In talking to machines, as with talking to any other party, diligence is the byword of effective communication. You have to instruct the machine how to count in terms that it already understands. There is no other way. And if that means building up an understanding to the point where a machine knows how to count, then diligence is going to be your constant companion. In this scenario, talking to machines is a lot like programming. And this is why programming is still so relevant in the world of information technology today. Because programming is a lot like talking to machines diligently.

In conclusion, this has been a circular kind of argument that has ended up almost where it began. Talking to machines is a lot like talking to people. You must share a language, so that each party is able to understand, and the language should be linguistic, so that each party is empowered to rationalize intentionality from a safe perspective. You must then attentively select the kind of information that you want to share and check that the machine understands you at every step. But unlike programming, the very act of talking to machines brings you to a closer understanding of their intentionality, and they to yours. When you get to the point where you’re able to ask the machine to count, you won’t need to know how it goes about it; you’ll just know that it can.

💬 Comments

Post comment